Immune cells attend a heart attack masquerade

Ischemic heart disease is the most common cause of death in the world, and it begins with the heart attack. Hearts attacks occur when a coronary artery becomes occluded and the heart muscle cells become starved of oxygen-rich blood and die. Immune cells respond to this by entering the dead tissue, clearing cell debris, and stabilizing the heart wall via fibrosis and repair. But what is it about dying cells in the heart that is so immune stimulatory? To answer this, researchers at CSB looked deep inside thousands of cardiac immune cells and mapped their individual transcriptomes using a method called single cell RNA-Seq. Now, in their recent Nature Medicine report, investigators describe the surprising finding that dying cell DNA mimics a virus, which causes immune cells to turn on an ancient antiviral program after a heart attack, even though there is no viral infection.

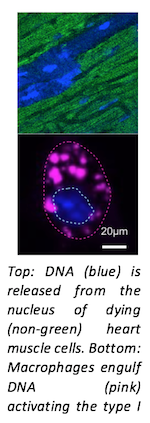

The immune system has evolved innate antiviral programs to defend against a diverse range of invading pathogens. Immune cells do this by detecting molecular fingerprints of pathogens, activating a protein called IRF3, and secreting interferons, which orchestrate a defense program mediated by hundreds of interferon stimulated genes. Investigators found that surprisingly, the antiviral interferon response is also turned on after a heart attack despite the absence of any infection. Their results point to dying cell DNA as the cause of this confusion because the immune system interprets it as the molecular signature of a virus.

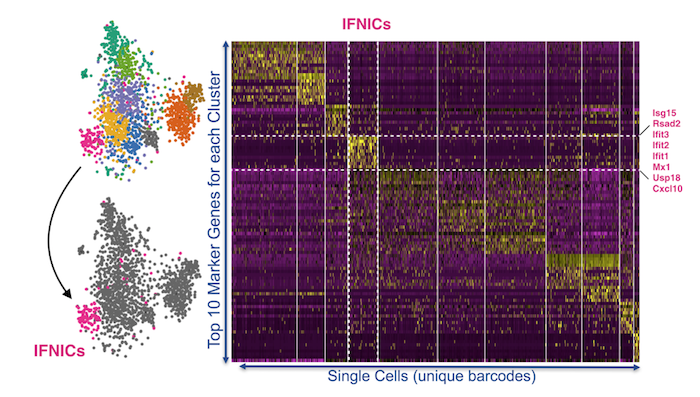

Surprisingly, the immune cells participating in the interferon response were a previously unrecognized subset of cardiac macrophages that the team named IFNICs for interferon inducible cells. These cells could not be identified by conventional flow sorting because unique markers on the cell surface were not known. Instead, the team had to look deep inside the cell using single cell RNA Seq, an emerging technique that combines microfluidic nanoliter droplet reactors with single cell barcoding and next generation sequencing. They examined expression of every gene in over 4000 cardiac immune cells and found the specialized IFNIC population of responsible cells.

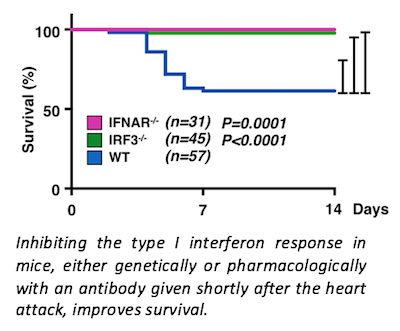

Is activating antiviral responses good or bad for the heart? Based on their data, investigators find that it’s bad since blocking it, either genetically or by giving an antibody after the heart attack, reduces inflammation and heart dilation and improves survival from 60% to over 95%. These findings uncover a new potential therapeutic opportunity to prevent heart attacks from progressing to heart failure in patients. Future studies will aim to better understand the interferon response and the IFNIC cell type and explore their roles in the infarcted and remodeling heart. The team is also working to understand the interferon response in other tissues and diseases where cell death occurs.

Future studies will aim to better understand the interferon response and the IFNIC cell type and explore their roles in the infarcted and remodeling heart. The team is also working to understand the interferon response in other tissues and diseases where cell death occurs

Article

IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction

King KR, Aguirre AD, Ye YX, Sun Y, Roh JD, Ng Jr RP, Kohler RH, Arlauckas SP, Iwamoto Y, Savol A, Sadreyev RI, Kelly M, Fitzgibbons TP, Fitzgerald KA, Mitchison T, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R

Nat Med, 2017;

Press Coverage

Immune Cells Mistake Heart Attacks For Viral Infections – EurekAlert! Science News

Myocardial infarct inflammation – Nature Immunology Research Highlight